The U.S. Department of Justice (“USDOJ”) has long made the fight against money laundering a central law enforcement priority. One of the primary areas where the USDOJ has focused its enforcement efforts is on financial institutions that either facilitate money laundering or fail to comply with U.S. anti-money laundering (“AML”) laws. In recent years, the USDOJ has expanded its enforcement efforts to non-U.S. banks, including securing a guilty plea and USD$2 billion penalty in December 2022 against a Danish bank. The USDOJ has also entered into several high profile resolutions involving Mexican banks. More recently, under the Biden Administration, the USDOJ has issued a series of policy announcements making clear that U.S. prosecutors will be focusing even more on foreign companies. Together, these developments have increased the risk of enforcement activities against Mexican banks. Given these increased risks, it is important for Mexican banks to understand how U.S. AML and other criminal laws may apply to them, and how the USDOJ’s framework for corporate criminal cases may impact the bank’s decision-making on risk and compliance.

This client alert will: (1) summarize the U.S.’s AML legal framework; (2) discuss the USDOJ’s corporate enforcement framework, including recent important updates; and (3) offer some takeaways for Mexican financial institutions seeking to mitigate the increased enforcement risks.

I. The U.S. Anti-Money Laundering Framework

To protect the U.S. financial system from being exploited for money laundering, in 1970, the U.S. Congress enacted the Bank Secrecy Act (“BSA”), which imposed on U.S. banks, money service businesses, casinos, and other financial institutions obligations to maintain anti-money laundering (“AML”) compliance programs and to file certain reports, such as suspicious activity reports (“SARs”). The BSA is enforced through civil enforcement actions brought by financial regulators, but also contains criminal penalties for U.S. financial institutions which commit willful violations of its provisions.

While the BSA does not apply to non-U.S. financial institutions, it is still relevant to Mexican banks for two reasons. First, the BSA will still apply to any U.S. branches of Mexican banks. For example, in 2017, the USDOJ entered into a non-prosecution agreement with the U.S. subsidiary of a Mexican bank for willfully failing to maintain an effective AML compliance program and willfully failing to file SARs in connection with USD$142 million in potentially suspicious remittance transactions. Second, where a U.S. bank is under investigation for suspicious transactions with a Mexican bank, that Mexican bank may become entangled in the investigation.

For example, in 2018, a U.S. bank agreed to forfeit more than USD$360 million and pleaded guilty to felony conspiracy charges for concealing deficiencies in its anti-money laundering program, specifically with respect to transactions at branches along the U.S.-Mexico border.

While the BSA is the primary tool used by U.S. law enforcement for AML, U.S. prosecutors have increasingly relied upon other U.S. federal crimes to charge non-U.S. banks with AML-related violations. For example, in December 2022, a global bank based out of Denmark pleaded guilty to a charge of conspiracy to commit bank fraud. As part of the plea, the bank admitted to defrauding U.S. correspondent banks by lying to them about the quality of its AML compliance program and the risk profile of its customers. The bank forfeited more than USD$2 billion to the U.S., in addition to another USD$850 million that the bank paid to resolve related investigations by the USDOJ and other authorities. The USDOJ has also relied upon U.S. money laundering laws to charge non-U.S. banks. For example, since 2020, the USDOJ has entered into non-prosecution agreements with two non-U.S. banks in connection with their involvement in the payment of bribes in the FIFA soccer scandal. In both cases, the banks admitted that they had engaged in an unlawful conspiracy to commit money laundering.

The prosecution of executives and individuals is another commonly employed weapon in the USDOJ’s toolbox to achieve its policy goals with respect to combating transnational corruption. Just last year, Hanan Ofer, who operated the New York State Employees Federal Credit Union, pleaded guilty to failing to maintain an effective anti-money laundering program in violation of the BSA. According to court filings, Ofer brought over USD$ 1 billion in high-risk transactions, including millions of dollars of bulk cash transactions from a Mexican bank, to the New York State Employees Federal Credit Union, without appropriate oversight or required reports. Ofer faces up to ten years of prison at sentencing.

Even where the USDOJ does not pursue criminal charges, it commonly seeks to use U.S. asset forfeiture laws to seize and forfeit property connected to criminal activity. This is notable because forfeiture actions may be exercised even if no criminal charges are ever brought. That is because the focus of the forfeiture action is on the criminally derived property itself. Funds in bank accounts are a frequent target of forfeiture actions. Mexican banks should be aware of the potential of forfeiture of their customers’ funds if they are within the reach of U.S. jurisdiction. Notably, in November 2022, the USDOJ for the first time successfully sought the forfeiture of property located in Mexico. In that matter, the USDOJ submitted a mutual legal assistance treaty request seeking to forfeit real estate located in Mexico connected to drug trafficking. A Mexican court invoked the country’s new civil forfeiture law to authorize the forfeiture of the property. This development portends more cooperation between the U.S. and Mexico on forfeiture actions.

Significantly, in 2021, the U.S. Congress adopted the most sweeping reforms to U.S. AML framework in two decades when it enacted the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (“AMLA”). Among other things, the AMLA expanded the USDOJ’s subpoena powers and established a beneficial ownership database. With respect to the beneficial ownership database, AMLA requires all private, for-profit entities that are doing business in the United States, not required to register with certain federal or state regulatory agencies, and employ less than 20 full time employees, to file a report identifying the company’s beneficial owners to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”). FinCEN is a bureau of the U.S. Department of Treasury, which collects and analyzes information about financial transactions to combat international money laundering, terrorist financing, and other financial crimes. With a beneficial ownership registry in place, enforcement agencies will be able to access information with a court order.

The AMLA also gives U.S. enforcement agencies the power to subpoena international financial institutions that hold correspondent accounts in the U.S, whether or not the information the authorities seek relates to the correspondent account in the U.S. Previously, the USDOJ or FinCEN could only issue subpoenas to request records limited to correspondent accounts of a foreign bank maintained in the U.S. The consequence of this expanded subpoena power is significant for Mexican banks that maintain correspondent banking relationships in the United States, because the changes allow federal investigators to obtain non-U.S. records through subpoena powers, rather than having to rely on international treaties and cooperation agreements. Failure to comply with a subpoena can lead to civil penalties of up to USD$50,000 per day and, if the U.S. government seeks an order from a U.S. district court, the foreign bank may be compelled to appear and produce records or be held in contempt of court.

II. The USDOJ’s Corporate Enforcement Framework

In 1999, the USDOJ adopted a policy governing corporate criminal prosecutions, which were adopted as the Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations. These policies set forth specific factors that U.S. prosecutors must consider in making charging decisions against corporations: (1) the nature and seriousness of the offense, (2) the pervasiveness of wrongdoing within the corporation, including management’s complicity or acceptance of the conduct, (3) the corporation’s prior history of misconduct, (4) the corporation’s willingness to cooperate with the government’s investigation of the wrongdoing, (5) the adequacy and effectiveness of the corporation’s compliance program both at the time of the offense and at the time the corporation is charged, (6)the corporation’s timely and voluntary disclosure of its own wrongdoing, (7) the extent of the corporation’s remediation, (9) the adequacy of civil or regulatory enforcement actions as remedies, (10) the adequacy of the prosecution of individuals responsible for the wrongdoing, and (11) the interest of any victims.

The USDOJ has also issued many other policies governing various aspects of corporate criminal cases, including how to resolve parallel investigations; how to credit corporations for voluntarily disclosing misconduct, cooperating, and remediating; when to seek independent compliance monitors; and how to evaluate corporate compliance programs. Over the years, the USDOJ has frequently revised these policies to encourage corporations to engage in behavior that is helpful to it.

Most recently, in January 2023, the USDOJ’s Criminal Division announced a series of significant revisions to its Corporate Enforcement Policy (the “CEP”) aimed at incentivizing more companies to make a voluntary self-disclosure (“VSD”), fully cooperate with the USDOJ’s investigation, and perform the timely and appropriate remediation of any compliance issues. Under the revised CEP, for companies that meet all three requirements, prosecutors will start with a presumption that the company will receive a declination, meaning that there will be no action brought by the USDOJ. If a declination is not appropriate (because of the presence of certain aggravating factors), then prosecutors will award the company a discount of between 50% and 75% off of the bottom of the fine range under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines. Given that criminal fines in corporate resolutions often reach nine—and even ten—figures, the discount can be significant.

III. The USDOJ’s Focus on Effective Compliance

One critical factor that the USDOJ will always consider is whether the company has implemented an effective compliance program. In assessing whether a compliance program is “effective,” the USDOJ instructs its prosecutors to ask three questions: (1) is the corporation's compliance program well designed? (2) is the program being applied earnestly and in good faith? And (3) does the corporation's compliance program work in practice? Thus, it is not enough for a company to have a comprehensive and well-designed compliance program on paper.

Under USDOJ policies, the failure to have an effective compliance program (or the failure to convince the USDOJ that a compliance program is effective) can lead to severe consequences for a company. First, it can lead to the USDOJ imposing an independent compliance monitor to oversee improvements to a company’s compliance program. Second, it can result in the USDOJ imposing a harsher form of resolution (such as a guilty plea) and/or larger fine. Third, it can result in the USDOJ extending the term of the resolution, or even lead the USDOJ to declare the company in breach of its agreement with the USDOJ. Lastly, the USDOJ has recently begun requiring that the Chief Executive Officer and Chief Compliance Officer both certify that their compliance programs are reasonably designed and implemented before releasing the company from their agreement.

IV. Takeaways for Mexican Banks

As cooperation between the U.S. and Mexico concerning AML regulation increases, Mexican banks face higher enforcement risks. The USDOJ is entitled to request information from Mexican banks via subpoena under the AMLA and through several cooperation agreements already in place (such as the Memorandum of Understanding executed in 2013 between the Mexican National Banking and Securities Commission). Furthermore, the U.S. and Mexican governments may be able to execute coordinated enforcement measures that result in more far-reaching consequences for Mexican banks currently under investigation.

The AML framework grants U.S. authorities a wide-range of powers and enforcement mechanisms that do not rely upon U.S. - Mexico cooperation. To mitigate risks under the current framework, Mexican banks should develop and implement specific compliance-based strategies, appropriate internal guidance and early response plans to cover situations in which Mexican banks may interact with the USDOJ. To obtain compliance credits under the CEP, Mexican banks facing a potential enforcement action may need to provide the USDOJ and other U.S. authorities with privileged and confidential customer records and information. Additionally, under AMLA, the US DOJ and other U.S. authorities may choose to seek information from Mexican banks via subpoena. Failure to fully cooperate and provide a proper VSD to U.S. authorities and failure to comply with a subpoena may result in penalties for non-compliant institutions.

However, compliance with these investigations might be challenging as Mexican banks are subject to bank secrecy and privacy obligations. Therefore, Mexican banks may be forced to grapple with the potential penalties and risks created by the conflicting provisions in the Mexican bank secrecy legislation and the U.S. AML framework. Accordingly, “enforcement risk” should constitute a key component of the Mexican bank’s internal risk assessment. For this purpose, Mexican banks should conduct a comprehensive analysis of their internal AML policies to identify risks and deficiencies in their compliance programs. As the USDOJ and U.S. regulatory authorities submit non-U.S. banks, especially Mexican banks, to investigations and proceedings in connection with AML laws, a well-designed, well-implemented, monitored and effective internal compliance program can help identify issues of concern before they create serious risks of enforcement. Further, an extensive and effective internal compliance network can help reduce penalties and minimize consequences when enforcement cannot be avoided. Mexican and U.S. legislation, international guidelines, and best practices provide sufficient tools to create and implement robust compliance programs that could potentially minimize or even exclude the banks' potential criminal, civil, and administrative liability.

If you have any questions concerning this Client Alert, please reach out to the following authors:

Paul Hasting, Washington D.C.

Leo Tsao, [email protected] +1 (202) 551 1910

Braddock J. Stevenson [email protected] 1 (202) 551 1890

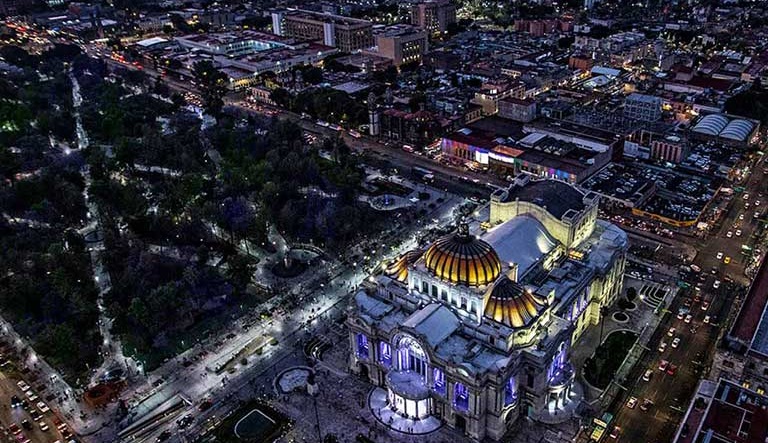

Ritch Mueller, Mexico City

See details below.